Should you use the competition’s brand name in your content to get more traffic?

Will this help or hurt you? Will you be able to “steal” traffic from the other guys or will it hurt you?

Sure, there’s value in bidding on a competitor’s brand name in PPC, but what about trying to rank for these branded keywords in organic search? Should you compete with direct competitors for their keywords?

This question has puzzled SEOs for a long time.

We decided to solve the puzzle the only way I know how — with lots of data based on keyword research.

We performed the first comprehensive study with a data-driven solution to this question: Should you use your competitor’s branded terms on your website or in your content to get traffic to your website?

Here’s what we wanted to discover

There are a couple different ways that an ecommerce business might want to use a competitor’s branded keywords as an organic SEO tactic.

One approach is selling a brand-name product. For example, an ecommerce site uses the keyword “Nike Air Zoom” on their product page to get more organic traffic from people who want to buy Nike’s Air Zoom shoe. Most ecommerce resellers use this technique.

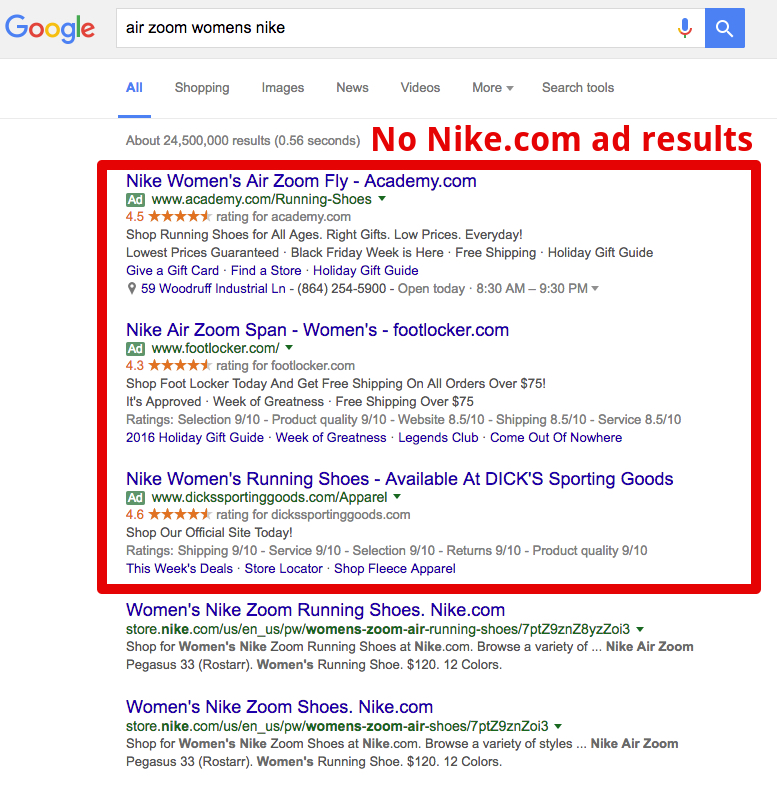

For example, look at this SERP for “air zoom womens nike.” The resellers are bidding on PPC results for the branded term.

But, keyword research proves that ecommerce sites don’t rely on PPC alone to get branded traffic. They can earn organic traffic, as well.

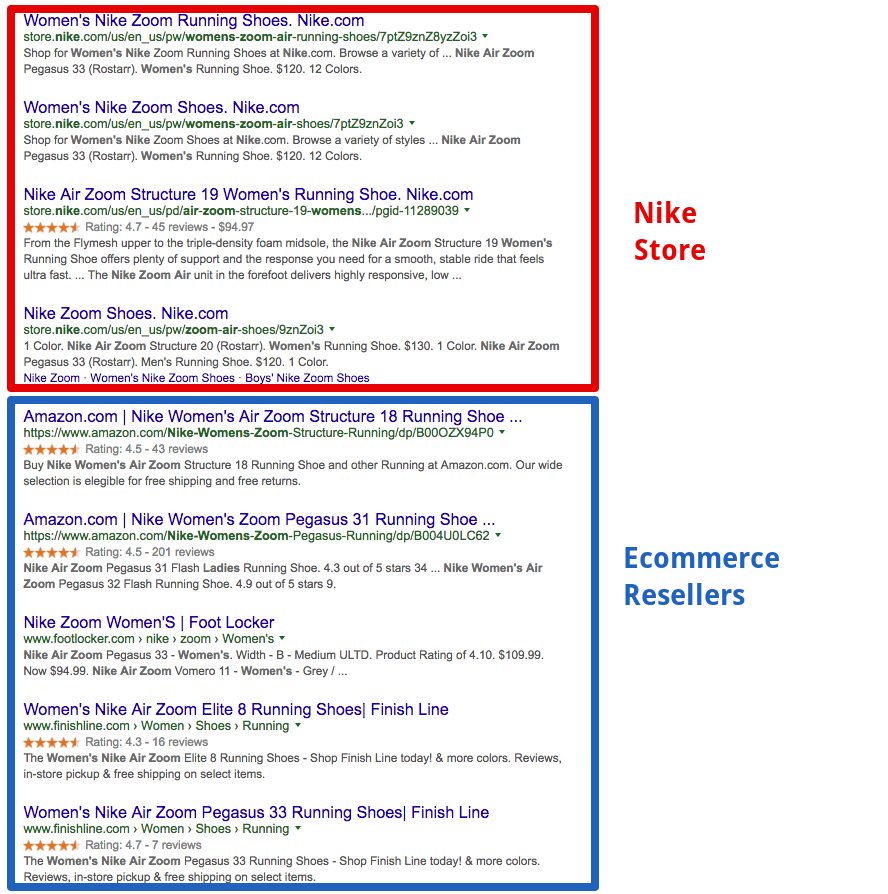

Here’s a screenshot of the same SERP, showing Nike with the top four organic positions, and ecommerce resellers holding the bottom five. (This SERP had only nine organic results, because of the placement of an image carousel in the bottom position.)

If you’re operating an ecommerce store selling Nike shoes, or Michael Kors handbags or Aeron chairs, then you should be using these branded keywords as part of your SEO strategy.

But, that’s obvious.

There are more complex levels of branded keyword usage that aren’t as obvious and the potential results are not as clear.

These are the questions that didn’t have clear answers to. We were determined to get answers, and keyword research and the related data, provided the answers to that query.

How we conducted the study

The issue becomes complicated, when you consider how variable branded terms are, what types of ecommerce businesses are trying to use them and whether the site using them is a direct competitor or an indirect competitor.

Another challenge in achieving a data-driven analysis is comparing the various types of ecommerce websites that might want to use branded keywords. Such sites would include review sites, how-to advice sites and coupon code sites.

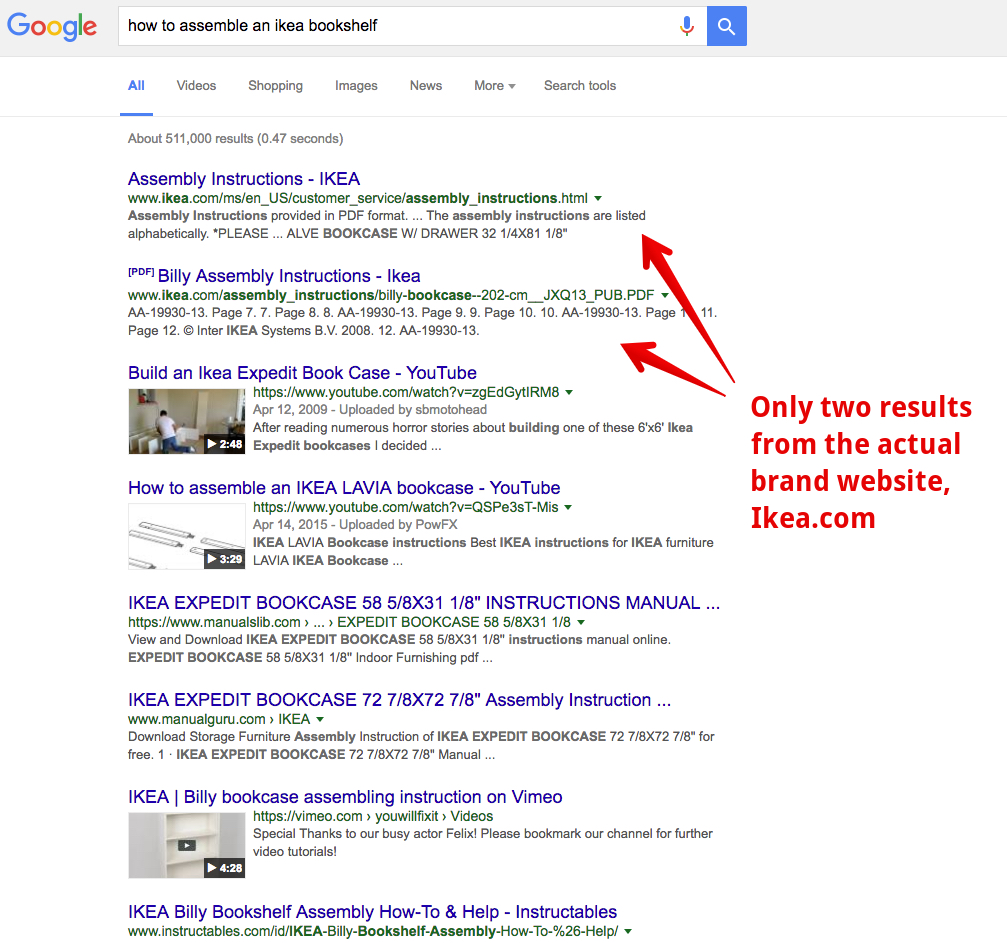

How to sites: How-to sites would use a branded term like “Ikea” to teach people how to assemble Ikea products. The website Sparefoot, for example, provides tips, pictures, and instructions for how to assemble Ikea products without stressing out.

In the SERP screenshot below, several YouTube results and manual websites are also appearing for “IKEA” branded keywords.

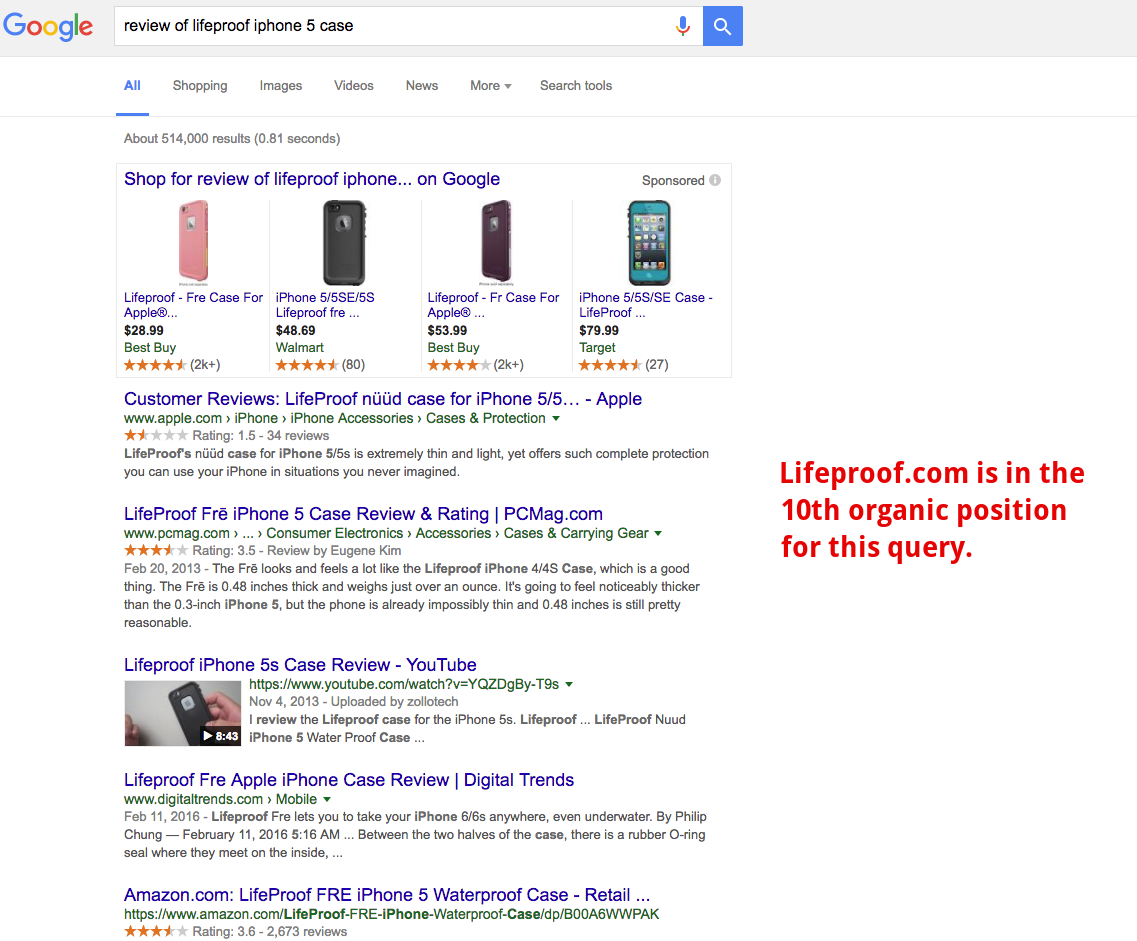

Review sites: Review sites are an important place for third-party reviews that require a business other than the brand to use the branded terms.

Notice how the organic results below, in which review sites such as Digital Trends are taking the top-rank for branded terms that are now their own.

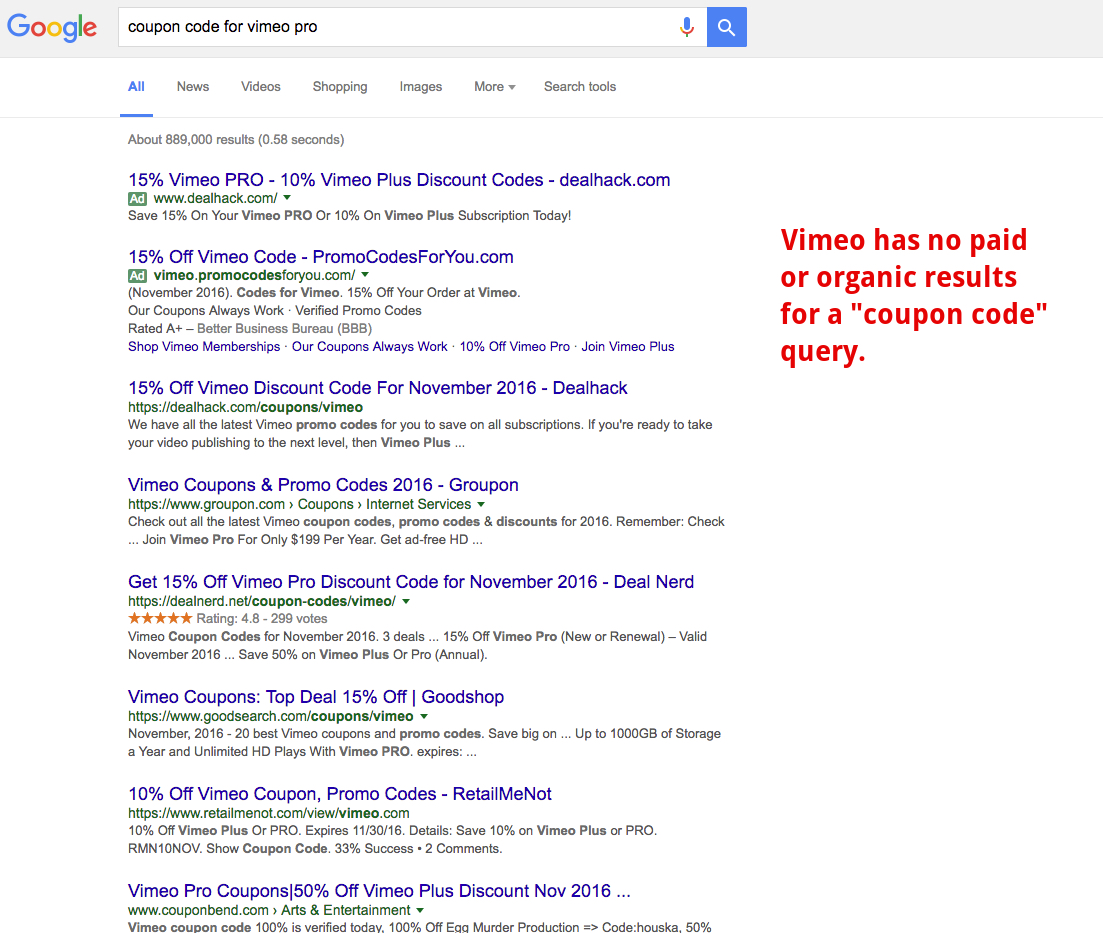

Coupon code sites: Coupon sites aggregate information about brands to help customers find discounts, so they have to use branded terms.

The organic results below, such as DealHack, show the rank tracker results for “vimeo” branded terms.

We had another challenge. How do we statistically normalize the vast amount of rank tracker signals between different ecommerce sites? Sites have low ranking and high-ranking for certain reasons.

What if a robust link building profile is producing their top-ranked position? Or, maybe it’s the depth and comprehensiveness of the content that’s giving it ranking power.

What we did to overcome these challenges was to select two of the largest ecommerce websites, Amazon.com and Ebay.com for keyword research and data analysis. These two sites would give us plenty of focused data, while also normalizing the range of rank tracker signals that would otherwise skew our data.

Analysis of Amazon.com

We conducted a comparative analysis of two data sets from Amazon:

- Keywords that contained the word “review.”

- Random keywords that did not contain the word “review.”

Comparing two groups of data would help us figure out if it’s worth it to try to organically rank for review-related keywords (or non-review related) keywords.

We counted keyword research regarding 41.4 million keywords that produced the top 100 Google search engine results for Amazon.com. The number of click-throughs from these SERP results was approximately 236 million.

We further segmented this dataset to analyze all keywords that contained the term “review.” There were 465,550 such keywords out of the 41.4 million. We pulled the 30,000 review keywords that produced the highest traffic volume for Amazon. We found that their median search engine volume was 140 searches per month.

For non-review keywords, we extracted an equally sized randomized selection of keywords that had the same keyword volume (140 searches per month).

We answered three data-focused questions for each of these two groups of keywords:

1. How difficult are these keywords to rank for?

This is the keyword research difficulty issue and we used SEMRush for our data. Other SEO tools, such as Moz and Ahrefs have metrics and algorithms that determine how difficult it is to rank for a certain keyword. It’s a really useful measurement when planning a content marketing campaign.

2. What is the CPC?

CPC or cost per click is helpful for knowing how competitive a certain search engine term is and how much you should bid.

For our purposes, we wanted to understand the median expenditure for the keyword group, to determine if it would be equally helpful to target these organically within search engines.

3. What is their competitive density?

Competitive density is similar to the “competition” column in Google Keyword Planner,” determined as “low,” “medium” or “high.”

This measurement determined how many advertisers are using that specific keyword in their ads. This metric would help us validate the monetary value of pursuing organic search engine results for ad-related terms. If the median results indicated a high competitive density, then ranking organically for the term in a crowded paid search environment would be difficult.

The highest level of competition is ranked as 1. Numbers closer to 1 (such as 0.9) would mean a high competitive density, but smaller numbers (such as 0.02) would mean a relatively low competitive density.

Answering these two questions for review keywords and non-review keywords would give us a strong understanding of how a site can rank for such terms and if it would be wise to do so.

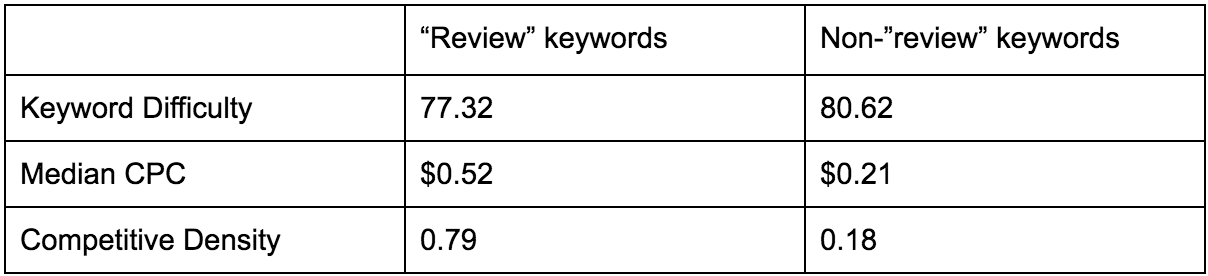

Here is our analysis.

Takeaways: Competitive density moves with CPC, so those two numbers will roughly parallel each other in the paid sphere. However, median keyword difficulty is where we identify the organic ranking potential of these terms.

Surprisingly, non-review keywords (those without brand names attached to them) have only half of the CPC value of branded keywords.

Even though these branded keywords are more valuable from a paid perspective, they are less difficult to organically rank for than their more expensive counterparts.

If we remove paid search and cost from the equation entirely, it would make sense for a business to focus their organic efforts within search engines on branded (non-”review”) keywords. They have higher transactional intent, greater overall value and an improved likelihood of ranking.

The takeaway from this data is this: Find branded keywords from your indirect competitors and target them in your content marketing.

Analysis of eBay.com

Our eBay analysis used the same methodology, but took a different angle in the analysis.

The keyword research set for eBay was smaller, so we used nearly all of the keywords (consisting of search engine volumes greater than 10/month) that directed traffic to eBay.com. This amounted to 21.2 million keywords. The median search engine volume was 40.

We analyzed two data sets:

- Non-branded keywords — those that did not contain any brand terms, including “ebay.”

- Branded keywords — keywords containing some brand name, such as “invicta” or “philadelphia eagles.”

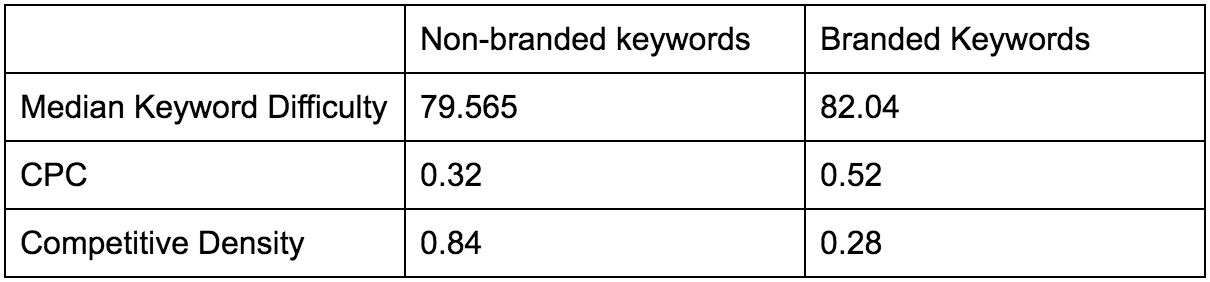

Here is how the two sets compare:

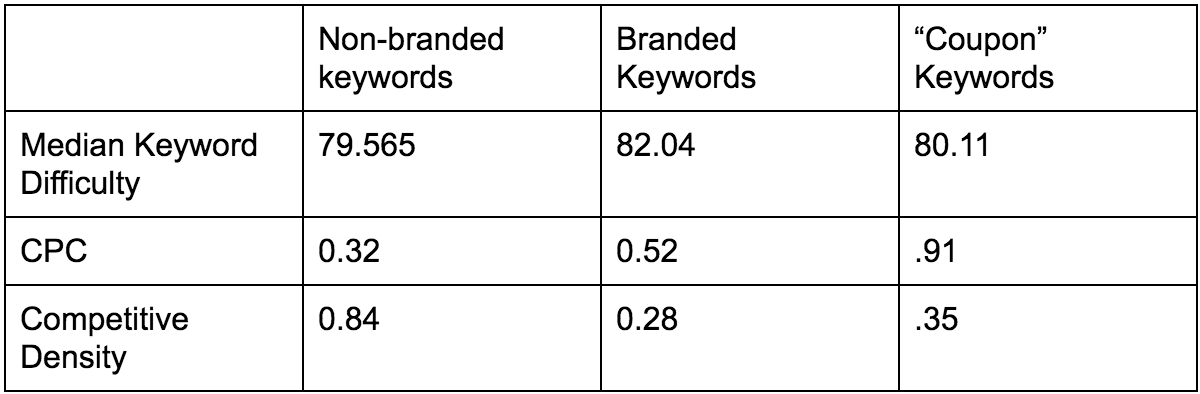

What’s the message shown in this data? Median keyword difficulty is roughly the same across all keyword types. If we consider the difficulty to be equal, then it makes sense to focus our organic search efforts on the most valuable keyword. We analyzed a subset, to understand how “coupon” keywords play into the mix. Here is what we discovered.

The most valuable keywords, as indicated by CPC, are the coupon keywords. These “coupon” insights are helpful, because a “coupon” keyword conveys clear intent on search engines. The user wants to buy something. Coupon keywords have a high likelihood of conversion, which is why they have high CPC bidding.

The other valuable set of keywords are branded terms. It makes good sense, both from a strategy and an effort perspective, to focus on those valuable terms that will help to convert more visitors into buyers.

How to Use Branded Keywords to Gain More Traffic to Your Site: A Step-by-Step Approach

The data tells us that it’s smart to use branded keywords in your organic search engine strategy. That brings up the obvious question. How?

First, here’s what not to do: All this talk about using your competitor’s branded keywords might make you think that you should target direct competitors.

You should not do this.

Why not?

Conversion Problems

First, because there is no reliable way to convert this traffic. If a user has a transactional intent on a given branded keyword, then he or she is expecting to carry through with that intent.

As early as 2008, Google recognized the importance that users placed upon brand and the weighted consideration that this had in perception and affinity. Eric Schmidt said, “Brand affinity is clearly hardwired. It is so fundamental to human existence that it’s not going away. It must have a genetic component.”

Whether you’re going to find the brand affinity gene or not isn’t the issue. The issue is that people do care about brands. If you rank for the brand of a direct competitor, this will not give the user a good experience.

Confusion Problems

Second, it produces brand confusion. Using a rank tracker for your direct competitor’s brand name may sound all sneaky and smart. But, in reality, it’s going to confuse people. To use an extreme example, why would the Adidas website come up when I google “Nike”? Did Adidas buy them out? Is Google choking on it’s own algorithm. The user gets confused.

Other Agencies Don’t Do It

Third, we didn’t notice any of the top marketing agencies doing this on their websites. As a corollary study to this one, we examined how some of the best online agencies were using branded terms in their content. We did not identify any instances where they were seeking organic traffic by using direct competitors’ branded keywords.

It’s too hard.

Ousting a brand from its top ranked Google position is nearly impossible. How do you outrank “CNN” for the term “CNN”? You can’t.

The trickle-down effect holds true in more diluted brand queries or long tails. When adding “coupon” or “review” to those branded terms, however, the game is wide open. As a simple rank tracker exercise will prove, anyone can rank.

So, what kind of branded competitor keywords should you use?

Indirect competition.

The ranking potential is higher, the value is greater and the results are much more appealing. Here’s how to do it.

How to identify your indirect competitors? – First, you need to figure out who your indirect competitors are. How do you find this out?

An indirect competitor is a business in the same industry that sells a different product or service.

Here’s how to find your indirect competitors.

- Conduct keyword research by Googling each one of your most important keywords.

- For each keyword, make a list of all of the businesses that have paid search engine results.

- From this list, identify those who are direct competitors vs. indirect competitors. You’ll recognize a direct competitor, because it’s a business that is selling the same product or service to the same market.

- Create a list of all of the indirect competitors for each keyword.

If you’re selling physical products on your ecommerce store, it might be difficult to find indirect competitors by simply Googling product-related keywords. Most of the paid results are ecommerce sites that sell the same product.

Instead, you may need to Google related keywords, using terms like this:

- [branded product] review

- [branded product] rating

- [branded product] coupon

- [branded product] customer reviews

- [branded product] benefits

Look at both the organic and paid results in order to find indirect competitors.

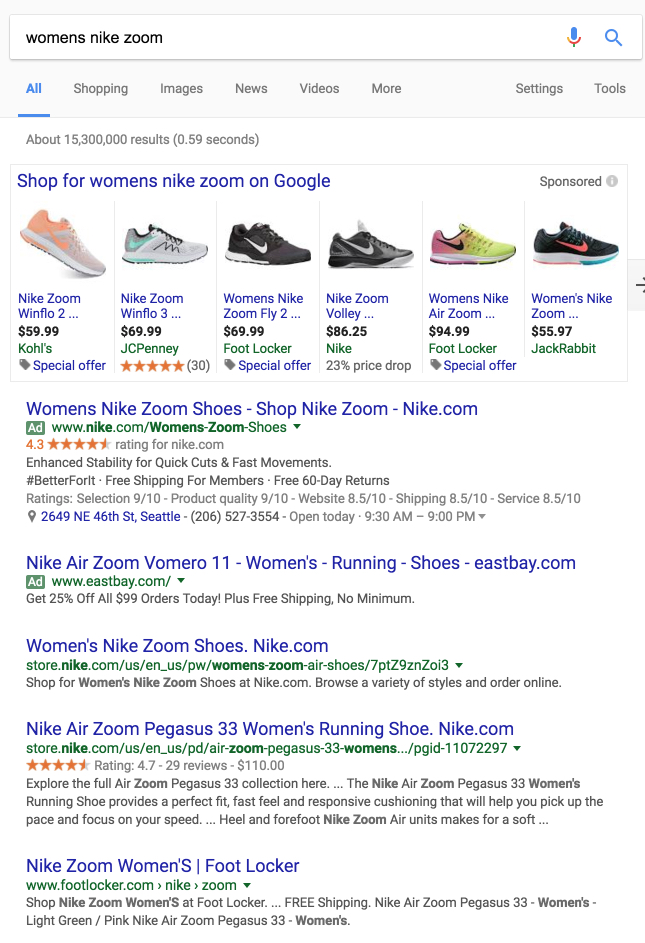

For example, let’s say I’m selling women’s Nike Zoom shoes on my ecommerce website. All of the paid search results are direct competitors.

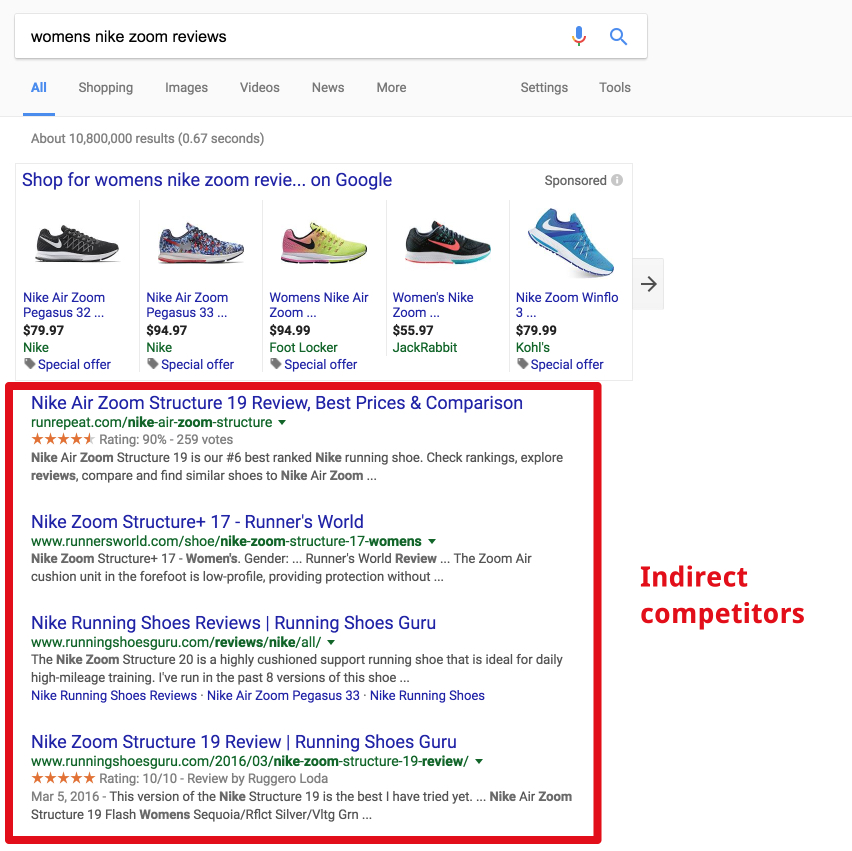

To find indirect competitors, I need to broaden my search engine results. This time, I search for “womens nike zoom reviews.”

The organic results display at least four indirect competitors.

Each of these sites do not sell the product directly, as I do with my ecommerce store. Instead, these sites publish product information and aggregate reviews. They also provide product comparisons and link building efforts which lead to ecommerce sites where the product is sold.

This is an example of an indirect competitor that is ranking for a “reviews” branded keyword.

Identify the branded keywords that are driving the most traffic to the competition – It’s your goal to steal as much traffic as possible from these indirect competitors. Since you offer a complementary product or service, users who search for the indirect competitor may be interested in your offering.

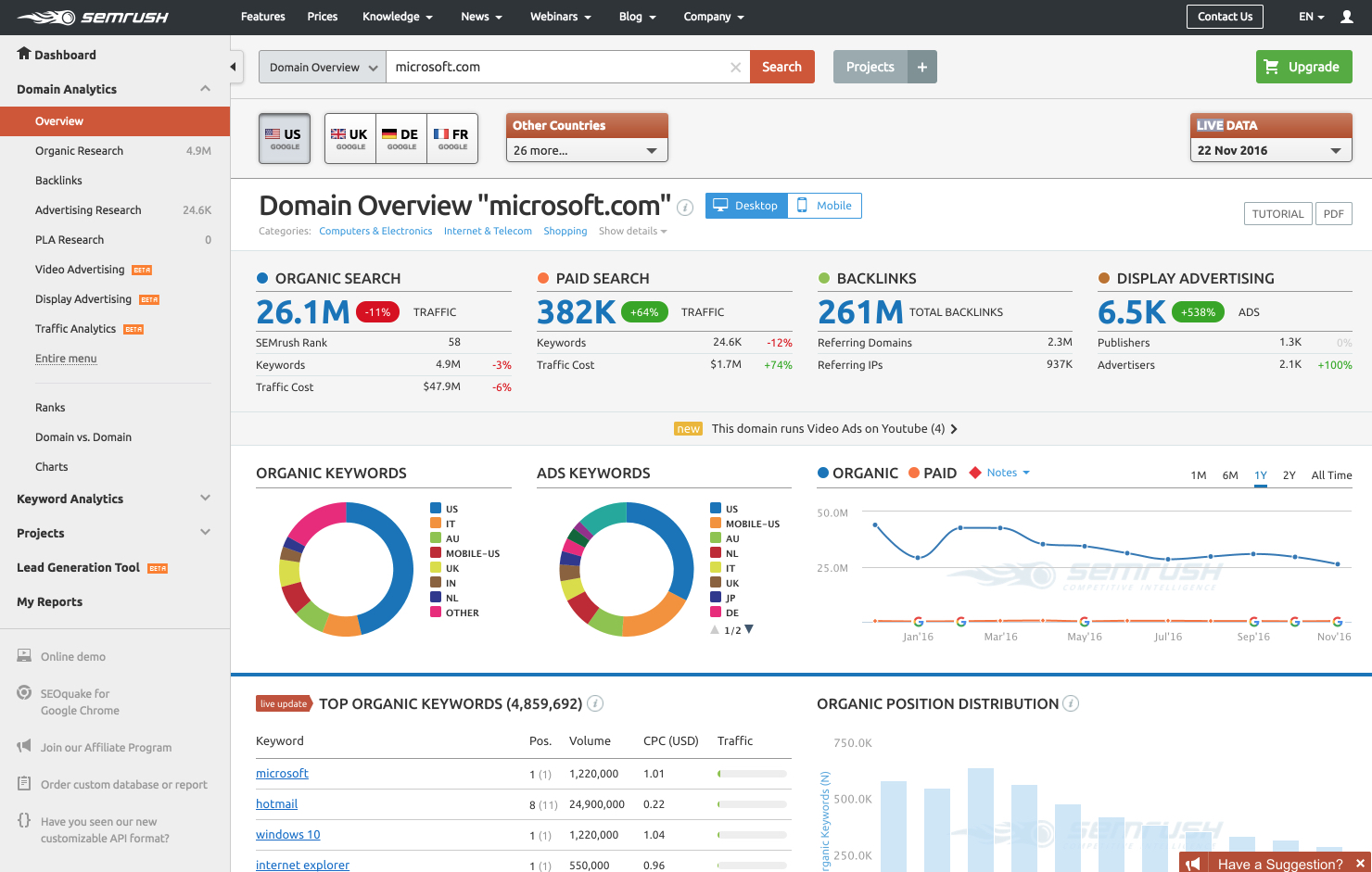

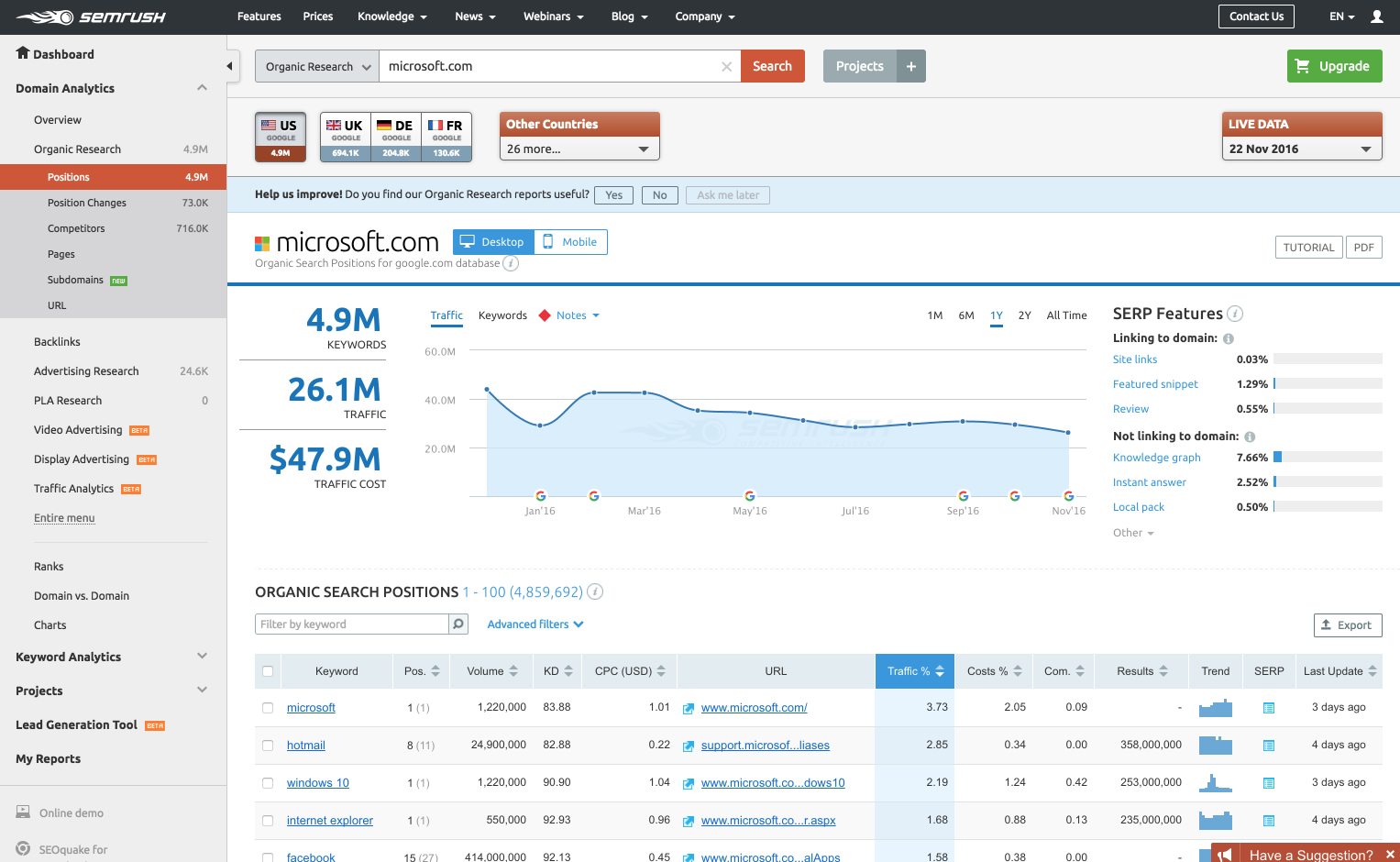

If you have an SEMRush account, open it up and enter the domain of your indirect competitor.

Scroll down to the “Top Organic Keywords” section. Click “Full Report.”

Notice all of the keywords that are branded. In the example above, each of the top websites (except Facebook) are MS-branded keywords: “Microsoft,” “Hotmail,” “Windows 10” and “Internet Explorer.”

If the website is small, you may be able to use all of the terms in the chart. If you’re dealing with a very large indirect competitor, then you should filter the keyword results or select a limited number to compete with.

Now, rank for these keywords. How? Use these keywords in your site content – Now that you have a list of your indirect competitors and all of their keyword targets, it’s time to use them on your own site.

Don’t just drop them carelessly into your content. Instead, you should create focused and comprehensive content that directly addresses a topic or concern about this indirect competitor or their branded product or service.

Remember, your goal isn’t to roast the indirect competitor. You might want to do a helpful review of their services or explain how their product benefits yours.

Make sure that your content is comprehensive and deep. This will dramatically improve your chance of gaining organic traffic.

Here’s a step-by-step strategy for ranking for these keywords:

- Take your list of indirect-competitor keywords and queries.

- Develop a piece of content around each keyword. Use the keyword as the subject matter, and develop the title around the keyword. For example, if you had the keyword “Windows 10” in your list, you could create a blog article titled “16 Advanced Customization Tactics for Windows 10 Power Users.”

- Discuss the keyword from every possible angle, making sure you use deal with any relevant topics. Using the Windows 10 example, you would research the topic thoroughly, and be sure to discuss topics and terms such as “theme,” “Cortana,” and “sync.”

- Make sure the content piece is at least 2,000 words long.

- Publish!

Track data and user engagement – It’s not quite enough to just write your piece and let it go.

If you’re tracking your keywords, for example, make sure that you add these new competitor branded terms to your keyword tool, to see how the content piece performs.

Conclusion

Here are the most important takeaways from our data analysis.

- Should you use the competition’s brand name in your website content to get more organic search traffic to your site? Yes.

- Will this help or hurt you? Help you.

- Will you be able to “steal” traffic from the other guys? Yes.

- Will it come back and bite you? Only if you target direct competitors.

It’s crazy to think that you can steal your indirect competitor’s traffic by using their branded keywords. But, it’s true. It works.

And, it’s not as hard as you might think!

Probably the most surprising takeaway from our data was this: it’s just as easy to rank for branded keywords as non-branded keywords, but twice as valuable.

Sure, I’m as eager to use paid search just as much as the next guy. It has its place. But, in the world of internet marketing, organic search still wins.

When we analyzed these 62.6 million ecommerce keywords, we didn’t know what we’d find. In the end, we answered all of our questions and gained some incredible insights.

Comments (164)