Growth hacking is an evolution.

Not a revolution.

It takes a different skill set. A new way of thinking.

However, at the end of the day, a lot of what you’re doing still looks and sounds like real marketing.

Not today’s misappropriated use of the word, but the good stuff originally developed back in 1960s.

Here’s why.

Where Did Growth Hacking Come From?

Sean Ellis gets credit for initially coining the term that would eventually send startup peeps into a frenzy. (And for the first time in their lives, not completely abhor the concept of marketing or sales.)

Sean’s concept came from initial failed attempts to hire data-driven, technical people focused on growing products or companies.

Instead, most of the ‘marketing backgrounds’ he saw made them great at communication, PR, and other classically defined marketing skills. Yet little focused on this new way of obsessing over conversions first.

These skill sets, while important, also aren’t completely necessary in very early stage startup companies, as QuickSprout excellently points out in the Definitive Guide to Growth Hacking. They also carefully point out that both skill sets are still very important – one’s just right for different circumstances.

But the problem comes when it’s asserted that growth hackers are fundamentally different than marketers. Even the sage Fred Wilson got this wrong.

Are the two things so interlinked really all that different?

I’m not so sure.

Here’s why, and where the confusion stems from.

The Great ‘Growth Hacking’ Hoax: Why Marketing Isn’t Advertising

It’s not growth hacking’s fault.

For years, ‘marketing’ has been masquerading as ‘advertising’. Inside most companies, the ‘marketing department’ does little more than work with advertising agencies or pick advertising channels.

Only in a rare case are they responsible for actual, you know, marketing.

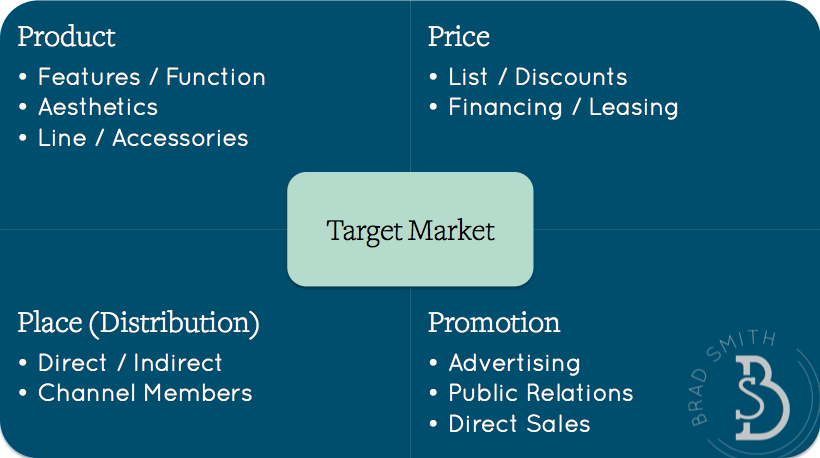

Years ago, like way back in the 60s, the marketing mix was developed to provide a framework of all the roles and responsibilities that marketing influences.

And what you’ll quickly notice, is that unlike today’s bastardized version of marketing, this one actually includes a few other key areas like Product, Pricing, and… wait for it… Distribution (we’ll come back to this last one in a minute).

Now is the marketing mix the end-all-be-all? Of course not. Sure, there’s flaws.

But the central idea is strong and valid. And it can be perfectly highlighted with a simple story.

Walk into any car rental agency right now. Or retail. Or food. Movie theater. Take your pick.

What you’ll encounter, is numerous dealings with the lowest paid, most underappreciated people in a company. And they’ll treat you as such. Your experience with each person (who undoubtedly hates their job and questions their existence) colors your worldview of that brand forever.

What do you call that? Who’s responsible for putting these ingrates in direct contact with customers on a daily basis? Customer service? Operations?

Now walk into an Apple store or a Four Seasons, and you’ll undoubtedly #humblebrag to your friends on Instagram how helpful and awesome they were.

That’s marketing. Even Fred Wilson readily admitted that customer service is one of the best forms of marketing for startups. And under the classic definition, it is.

The long-winded point here is that true marketing isn’t advertising. Or PR. Or sales. It’s all this junk that ultimately gets a customer to buy your stuff.

Or ‘convert’ and become a ‘user’.

Peter Drucker, the OG, said the “aim of marketing was to make selling superfluous”. Obviously that’s not defined or limited to a single person or department within an organization. And that’s where the confusion stems from.

Growth hacking definitely has some unique characteristics that make their objective different than say, these other brand marketers who obsess over fuzzy intangibles all day.

But at the end of the day, a lot of what they do still looks like classic marketing.

Let’s get specific.

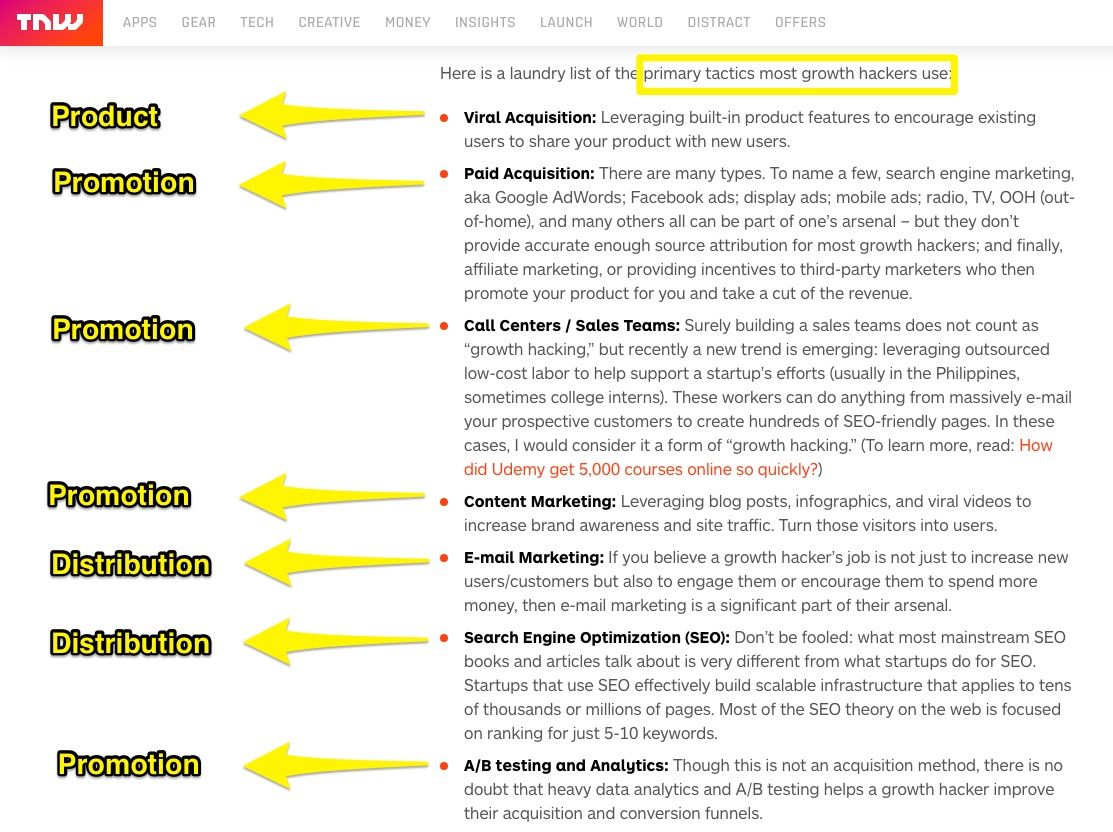

If you try researching the difference between marketing and growth hacking, you’ll see this article from The Next Web. A reputable, tech savvy site that’s going to finally lay the issue to rest. Perfect.

And it’s a good read, which culminates in pointing out the laundry list of tactics that commonly differentiate growth hacking from marketing.

However, when you really start to analyze these tactics under a broader understanding of what marketing is or involves, you’ll quickly start to see that these new-fangled tactics still look a whole lot like mid-century marketing.

When you get right down to it, a lot of the daily activities that define growth hacking resemble much of the same seemingly outdated marketing concepts from nearly 50+ years ago.

Again, let’s get specific.

Let’s take a look at some of the most fundamental ‘growth hacks’ used by successful startups over the past decade to reverse-engineer their meteoric rise.

Example #1. Product Hacks

Long before Gmail, there was Hotmail.

The idea of free email, at the time about twenty years ago, was kinda nuts. And it also presented a few obvious drawbacks to classic growth methods like advertising.

(Yes, even Stone Age Startups understood how CAC affects LTV. That wasn’t just a YC thing for you millennial hipsters.)

Instead, Hotmail decided to leverage their existing 20,000 user base to kickstart one of the first examples of ‘viral acquisition’.

In the bottom of each email, they added the simple tagline: “Get Your Free Email at Hotmail”.

Commonplace now, but keep in mind that this simple edit was pretty revolutionary at the time. Within six months, their userbase shot up to a million users.

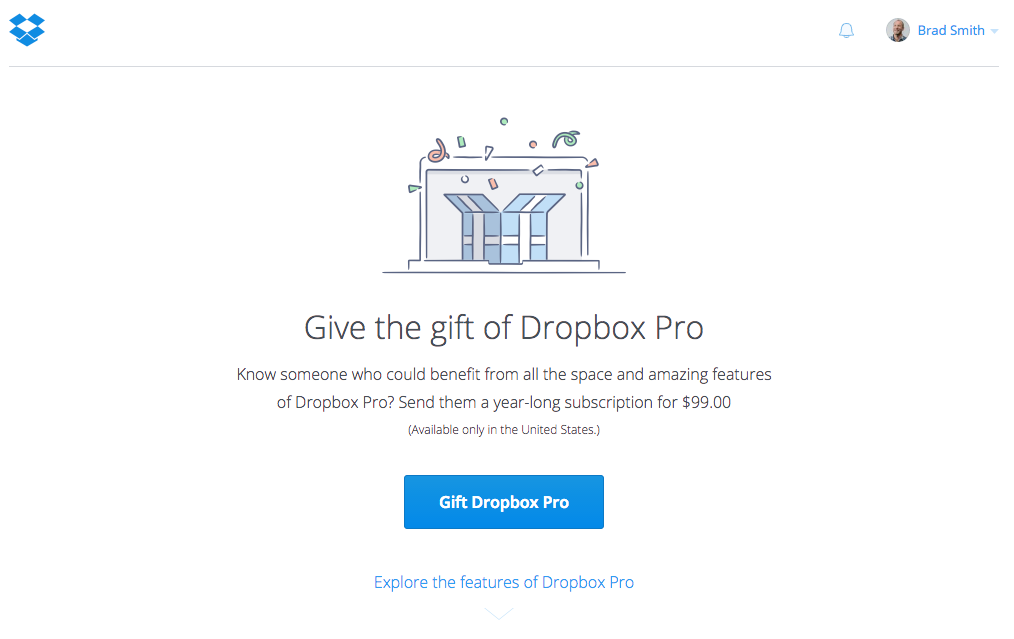

Fast forward a bit, and another Silicon Valley darling was quickly finding out that paying more for a new customer than they’re worth is a recipe for disaster (and bankruptcy).

In response, they created a simple referral program that resembled Hotmail’s early tactic. Each new person that signed up for an account through this referral process got 500MB of free storage.

And in a little over a year, Dropbox grew from 100,000 users to 4 million.

Now there are many reasons these tactics succeeded. For one, getting something (for free) from your friend is a more compelling proposition than buying from a stranger over a questionable banner ad.

However, these are still simple product decisions too at the end of the day. (1) You have to have a good product to begin with – otherwise all the Promotion in the world won’t help. And (2) creating new features in the product are what enable it to be shared through a referral mechanism.

But it also brings up an important concept from, you guessed it, the 60s.

In marketing promotion, there’s Reach. And Frequency.

- Reach: The number of new, unique people your message is seen by.

- Frequency: The number of times that message reaches these people.

Admittedly, very simple. But also effective.

You’ll notice that in both cases, Hotmail started with an initial 20,000 users while Dropbox had 100,000. If you’re going for viral growth through recommendations, you need an existing user base to tap.

Why? Reach and frequency.

Wanna make numbers go up? Increase those two things.

The first is pretty easy. Just get more eyeballs to see your message.

Here’s how.

Example #2. Distribution Hacks

Back in the day, distribution used to be more focused on Place.

That’s because we lived in small towns and cities where you literally had a physical storefront. And even when times evolved, when products needed to be shipped across different factories or warehouses or retailers, you relied on heavily on distribution.

Technically, it means the “process of making a product or service available for use or consumption by a consumer or business user, using direct means, or using indirect means with intermediaries”.

That brought about different distribution methods like intensive, exclusive or selective (all of which mean exactly like they sound).

Today, this all seems archaic because you’re mainly going direct to consumers through the interwebs.

But here’s the important part, summed up by Wikipedia:

“The role of the marketing channels is not only focus on the participate in demand satisfaction by offering goods, but also need to stimulate demand through information, creating proximity and promotion by customer (Balasecu, 2014). In other words, distribution channels for the product is a system process.”

Distribution hacks are some of the most common in growth hacking lexicon, and its roots are still firmly planted in the work from previous decades.

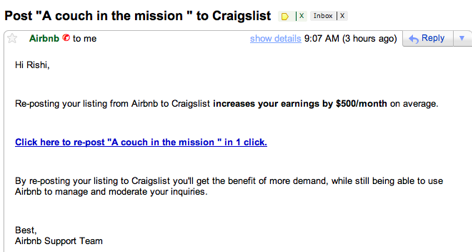

Airbnb didn’t magically become the one-stop shop for letting strangers crash on your couch. No; they ‘borrowed’ (or ripped off) Craigslist’s user base (thereby massively extending their own distribution). They created simple tools to allow Airbnb users to also get their properties in front of the massive number of people already searching and browsing Craigslist.

This approach is nothing new.

Back in the good old days, YouTube used a similar form of ‘platform hacking’ (read: distribution) to piggyback on MySpace’s success (and userbase of around 25 million uniques in 2005). Unlike many other video platforms at the time, YouTube openly allowed (and encouraged) users to take advantage of their embed code and spread their content to larger platforms like MySpace.

Facebook used selective (or exclusive) distribution when they started off as a closed network only open to specific colleges. That exclusivity idea was then borrowed by Pinterest who initially used invite-only status to increase their desirability and cachet.

In each case, distribution – a classic marketing consideration – was central to growth.

Example #3. Promotion Hacks

Despite the semantic issues already discussed at length, advertising still plays a role in today’s ‘growth hacking’ playbook.

Look no further than Eric Ries’ Lean Startup (which I can’t believe was published in 2011 already), where advertising shows up as one of the three engines of growth to grow a sustainable business.

Paid acquisition, once again, isn’t some completely brand new concept that evolved from the halls of MIT or Stanford. Instead, it’s been employed successfully for half a century since the Mad Men era.

Sure, advertising channel options were incredibly limited back then. Which meant it was far easier to get your stuff to stick out. And sure, they didn’t have fancy cohort analyses or funnel tracking tools, instead largely relying on correlation measurements to sales.

But still.

Make more money than you spend ain’t an original equation. And it’s especially useful in today’s world, where let’s face it: true virality like some of the earlier examples is incredibly rare (not to mention, borderline lucky).

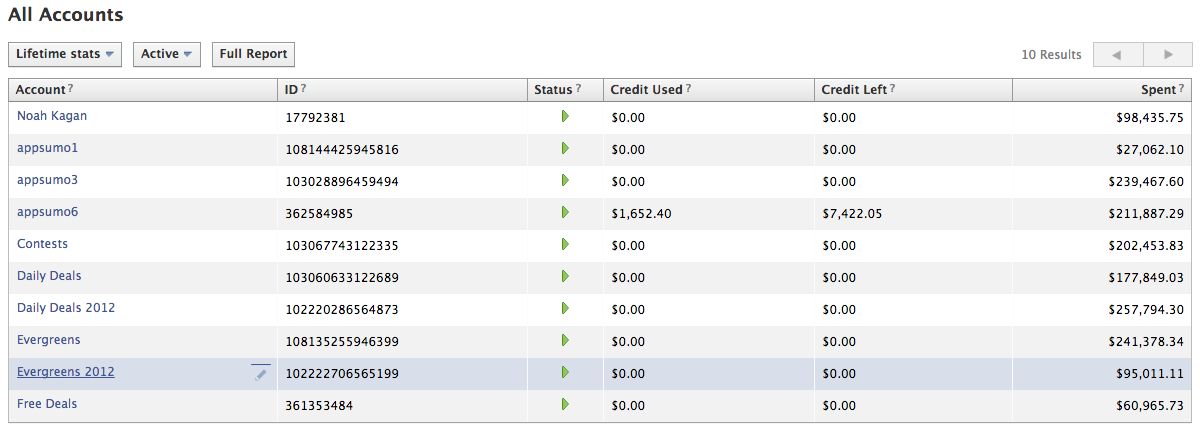

Just look at Noah Kagan at AppSumo, who has spent over $2 million on ads to profitably grow their business.

Or Netflix spending around $18 bucks for a subscriber when they make like $300 on each.

Or Groupon.

(Don’t laugh. They still went public, bro.)

Sure they spent a sh*t-ton to do it, reportedly almost $200 mill in a single quarter according to the SEC. But that also helped them gain 33 million new subscribers. AND GO PUBLIC.

Point is: paid acquisition isn’t a ‘hack’. It’s just called good (read: not terrible) advertising.

A few minutes ago you read about Reach, which can be increased through distribution and obviously advertising.

However advertising can also help bolster Frequency, which is important considering its curse (as Seth Godin describes it):

“The best members of your audience, the ones who are listening the most carefully, have to be bored/annoyed at the messages that show up after they take action. Some people pledge the first day of pledge week, or buy the book the day it comes out. Those folks don’t want or need to hear the message again.”

“Worse, frequency creates a culture of less engagement. Since we know that just about every important issue, opportunity or warning is going to be repeated a few times, we don’t engage as much. Why bother to listen, we say, they’ll just repeat it.”

The world ain’t as simple today as it used to be. A single ad or message won’t get someone to convert.

But multi-channel marketing, complete with remarketing ads or utilizing custom audiences on Facebook, provide another new twist on an old stand-by marketing principle.

Conclusion

Growth hacking can involve mind numbingly complex techniques to obsessively grow a new product.

It’s difficult to pull off and takes truly creative thinkers who’re able to blend strategy with technical chops.

But at the end of the day, a lot of what they’re doing still sounds a lot like marketing when you think about it.

Not today’s watered-down version of advertising or PR. But true marketing, how it was envisioned over half a century ago, at its theoretical high point.

Those days weren’t perfect. And the models espoused can seem a bit dated at times.

However, you might be surprised to find that your new brilliant growth hacking idea didn’t come from hitting refresh on Hacker News, but instead from looking through a few dusty books from the 60s.

About the Author: Brad Smith is the founder of Codeless, a B2B content creation company. Frequent contributor to Kissmetrics, Unbounce, WordStream, AdEspresso, Search Engine Journal, Autopilot, and more.

Comments (6)