As marketers and business owners, you will most likely come to deal with the process of pricing your products or services.

The thing is, many folks struggle with this process because although they understand their customer’s needs, they aren’t experienced with what to charge people for their work.

Below I’ve analyzed a few recent research studies that dive into pricing of products and services in the hope that you might better understand how to price your own goods.

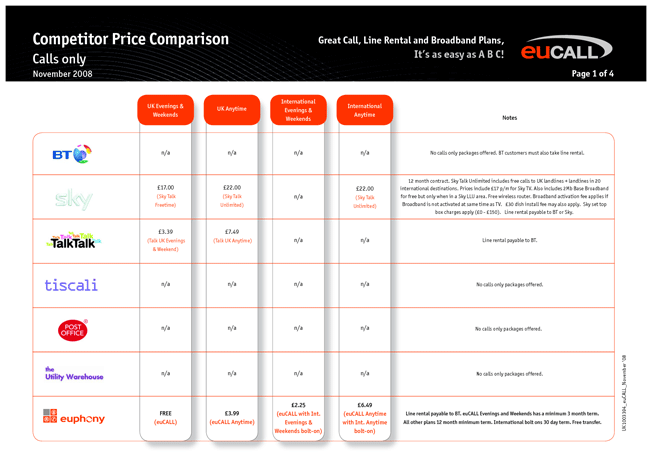

1. Comparative Pricing: Not Always Optimal

One of the first techniques that many marketers attempt in forming a new pricing strategy is to directly compare their price with that of a competitor.

“Hey, my software is 30% less than this popular option, why not buy mine?”

The problem is, comparative pricing isn’t always as reliable as marketers think it is, and can effect costumer’s perceptions of the product in a few different ways.

Consider this scenario: Buying Aspirin…

You walk into a drugstore and see the familiar sign inviting you to compare the price of the store’s brand of aspirin to a national brand.

What do you do?

According to Itamar Simonson, you may not go for the cheapest.

Instead, you may choose the major brand because you perceive it as the less risky choice. Or you may not buy anything at all.

This new research from a Stanford marketing study has shown that asking consumers to directly compare prices may have unintended effects.

Simonson found comparative pricing isn’t always favorable because “it can change the behavior of consumers in very fundamental ways.”

Consumers may decide not to buy at all or to minimize what they perceive as a heightened risk instead of following the advice that the marketer had in mind.

This study analyzes the effect of implicit and explicit comparisons to arrive to this conclusion.

Implicit comparisons occur when a customer takes the initiative to compare two or more products.

Conversely, explicit comparisons are those that are specifically stated or brought up by the marketer or advertiser.

To test the effects of comparative advertising, Simonson & Dholakia set up two trials.

The first involved selling CDs on eBay.

The researchers listed (for sale) a number of top-selling albums in CD format, such as “The Wall” by Pink Floyd (hey, not too bad of taste either ;)).

The cost of the CD’s put up for sale always started at $1.99.

They then “framed” these auctions in two very distinct ways.

The first way had the CD ‘flanked’ with two additional copies (of the same CD) that had a starting bid of $0.99.

The second had the original CD flanked with two copies starting at $6.99.

The results seemed clear: The CDs flanked with the more expensive options ($6.99) consistently ended up fetching higher prices than the CDs next to the $o.99 offerings.

“We didn’t tell people to make a comparison; they did it on their own,” said Simonson.

“And when people make these kinds of comparisons on their own, they are very influential.”

In order to test the effects of explicitly telling the consumers to compare, the researchers re-did the experiment with the same settings, only this time they outright asked consumers to compare the $1.99 CD with the other offerings.

The results of this showed that when explicitly stated to compare, prices of the adjacent CDs became statistically irrelevant to what the bids were on the middle disc.

Additionally, buyers became much more cautious and risk adverse in their purchasing of the CDs:

“The mere fact that we had asked them to make a comparison caused them to fear that they were being tricked in some way,” said Simonson.

The results were that people became more timid in every aspect imaginable: fewer bids, longer time on their first bid, and less of a likelihood to participate in multiple auctions.

“Marketers need to be aware that comparative selling, although it can be very powerful, is not without its risks.”

Think about that the next time you directly compare your offering to your competitors.

Instead, you might better benefit from highlighting unique strengths and placing an emphasis on time saved over money saved…

2. Selling Time Over Money

“It’s Miller Time.”

For a company selling beer, this type of slogan might come off as somewhat of an odd choice.

But according to new research which advocates the benefits of “selling time” over money, it may be a perfect choice.

“Because a person’s experience with a product tends to foster feelings of personal connection with it, referring to time typically leads to more favorable attitudes—and to more purchases.”

So says Jennifer Aaker, the General Atlantic Professor of Marketing at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Why would selling experience (or time spent) with a product work so much better in some instances than discussing the products favorable price?

Aaker noted that many (around 48% of those analyzed) advertisements included a reference to time, noting that many marketers seem to innately understand the importance of time to a consumer.

Unfortunately, very little in the way of actual studies had been done to back this up.

In their first experiment addressing this, Aaker and her co-author Cassie Mogilner set up, of all things, a lemonade stand using two 6-year olds (so it would appear legitimate).

In this experiment, the lemonade sold could be purchased for $1-$3 (customer selected) and a sign was used to advertise the stand.

The 3 separate signs to advertise the lemonade were as follows:

- The first said, “Spend a little time and enjoy C&D’s lemonade”

- The second said, “Spend a little money and enjoy C&D’s lemonade”

- The third said, “Enjoy C&D’s lemonade” (neutral sign)

Even with this lemonade example the results were apparent.

The sign stressing time attracted twice as many people, who were willing to pay twice as much.

To further drive this point home, a second study done with college students (and iPods) was conducted.

This time, only two questions were asked:

- “How much money have you spent on your iPod?”

- “How much time have you spent on your iPod?”

Not surprisingly considering the last study, students asked about time demonstrated far more favorable opinions of their iPods than those asked about money.

The researchers thought that:

One explanation is that our relationship with time is much more personal than our relationship with money.

“Ultimately, time is a more scarce resource—once it’s gone, it’s gone—and therefore more meaningful to us,” says Mogilner.

“How we spend our time says so much more about who we are than does how we spend our money.”

Aaker and her colleague were not done yet, however.

Determined to test whether or not all references to money would lead to a more negative output (due to the participant being reminded of how much they spent on a product), they conducted a similar experiment at a concert.

This time, the “cost” was actually time, as the concert was free, but people had to “spend” time in line to get the good seats.

The two questions asked by the researchers in this scenario were:

- “How much time will you have spent to see the concert today?”

- “How much money will you have spent to see the concert today?”

The results?

Even in an instance like this, where time was the resource being spent, asking about time increased favorable opinions toward the concert.

Not only that, people who stood in line the longest, or the people who incurred the most “cost”, actually rated their satisfaction with the concert the highest.

“Even though waiting is presumably a bad thing, it somehow made people concentrate on the overall experience,” says Aaker.

So what’s the deal here?

Marketers need to start being aware of the meaning that their products bring to the lives of their customers before they start focusing their marketing efforts.

And one more thing to think about…

The study notes that the one exception seems to be any products consumers might buy for prestige value.

If you aren’t in the line of selling sports cars or tailored made suits, you most likely won’t have to deal with this, but the point remains:

“With such ‘prestige’ purchases, consumers feel that possessing the products reflect important aspects of themselves, and get more satisfaction from merely owning the product rather than spending time with it,” says Mogilner.

Factor these considerations of the important of time next time you go about pricing your product, and you’ll see that catering to consumer’s most precious resource, their time, can be more persuasive than even the most drastic of price reductions.

3. Effect of “Useless” Price Points

In addition to the above, you will find that the differences between your pricing points are going to greatly affect your customer’s perceived value of your product (and how they convince themselves of what to buy).

The video below, Dan Ariely describes the pricing situation encountered over on The Economist.

Dan realized that there were 3 very peculiar price points:

- A web-only subscription for $59

- A print-only subscription for $125

- A web + print subscription for $125

Daniel notes that this doesn’t make sense, as option 2 seems “useless” in that you’d be better off getting the print + web for the same price.

He follows up with an interesting study that examines what would happen if he took out the middle price:

His findings?

The price in the middle, while seemingly “useless” in that it didn’t provide any value (since the print + web was the same price) was actually useful in that it helped get costumers to turn from “bargain hunters” to “value seekers”.

What was happening was that customers began to compare the middle option to the latter option (since their prices were similar) and this comparison made option 3 look like an excellent deal.

Without the middle option, we can see that the price points set by the economist had too much contrast: when the middle option was taken away, people looked at the two prices and tried to convince themselves that they didn’t need the “upgrade”.

Essentially, they became “bargain hunters” rather than “value seekers” which are the kind of customers you really want.

With appropriate pricing in place, you can offer customers options that fit their budget, while at the same time influencing “on the fence” customers that your more premium offerings give enough benefit that their extra price is justified.

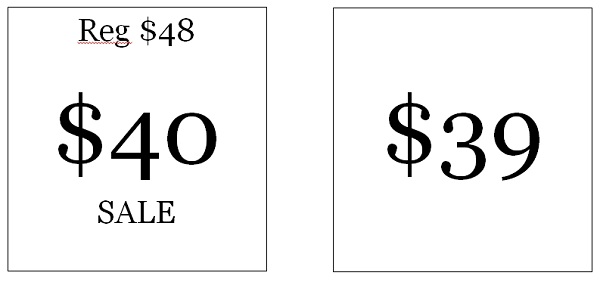

4. The Power of Number 9

Head over to practically any store around (online or brick and mortar) and you’ll see prices that end in “9” everywhere.

We’ve all heard of the reasons why it’s used (to make the price look lower), but does it really work? Are people really going to be effected by a $99 price point versus paying $100?

As it turns out, this tactic does indeed work, and has been dubbed the use of “charm prices.”

In his book Priceless, William Poundstone dissects 8 different studies on the use of charm prices, and found that, on average, they increased sales by 24% versus their nearby, ’rounded’ price points.

In fact, in an experiment tested by MIT and the University of Chicago, a standard women’s clothing item was tested at the prices of $34, $39, and $44.

To the researchers surprise, the item sold best at $39, even more than the cheaper $34 price.

One has to wonder… is there anything that can outsell number 9?

Researchers have found that sale prices, that emphasize the original price, do seem to beat out number 9 when split tested.

In the image below, the price point on the left won:

So, apparently 9 can be defeated with a sale price…

Not so fast!

The number 9 still comes out on top when it is used in cohesion with a sales price.

In another split test, the sale prices was used ending in ‘9’, and it ended up performing best of all:

And there you have it.

Given similar circumstances, given even a less expensive option, it seems that the power of 9 still takes hold; remember that when setting pricing of your own.

5. The Price Perception: Context Matters

In a pricing experiment conducted by Richard Thaler, two scenarios were tested for a relatively mundane exercise: buying a friend a beer on the beach.

In the first scenario, the participant was asked by a friend if he wanted a beer, and it was specified that the beer was going to be bought by the local rundown grocery store.

In the second scenario, the beer was going to be purchased by the nearby posh hotel.

Keep in mind the interior of the hotel had nothing to do with the results, the beer was to be imbibed on the beach.

Thaler concluded that it simply strikes people as being unfair that they should pay the same for both places, even though the beer itself is exactly the same.

One might also recall the case study from Robert Cialdini’s ‘Influence’, where is discusses how a local jeweler managed to sell out of turquoise jewelry because it was accidentally priced at double its initial price, instead of half (which is the price she had intended).

The inflated price now made the jewelry irresistible to buyers, who had before ignored the color over all others (which was the initial reason for the intended price cut).

Now that the price had been raised, the context of turquoise jewelry had a “high value” in the buyer’s minds, even without an explanation!

When it comes to price, priming is also heavily influential: a $60 dinner doesn’t sound so bad when anchored next to a $300 dinner.

Similarly, the best way to sell a $3,000 suite is to put it next to a $10,000 suite!

Even if you don’t intend to make a large sales volume from premium items, their presence alone can help the anchoring effect take hold and increase conversions on the product you are really aiming to sell en masse.

Over To You

Which of these research studies was the most surprising to you?

How do you think you will be able to implement some of their findings into your own business?

Thanks for reading!

About the Author: Gregory Ciotti is the founder of Sparring Mind, the blog that takes psychology + content marketing and makes them play nice together. Download his free e-Book on ‘Conversion Psychology’ if you’d like more information!

Image Credit: Images for the “Number 9” example above are from ConversionXL

Comments (79)